By Robert L. Harrison and Larry Clinton, Sausalito Historical SocietyThe following is a lightly edited excerpt from an essay by Bob Harrison for the Anne T. Kent California Room:

In the early 20th century, long before there was a Golden Gate Bridge, the ferry connection between Marin County and San Francisco was a dominant factor in Marin’s development. Tiburon and Sausalito competed to become the principal site for this connection. Both towns were 6.5 miles across the Bay from San Francisco, and both were railroad terminals serving Marin and locations to the north.

Marin’s two railroads provided extensive wharves and marine support services as well as direct ferry service to San Francisco. In 1907 these lines were merged to form the Northwestern Pacific (NWP) Railroad.

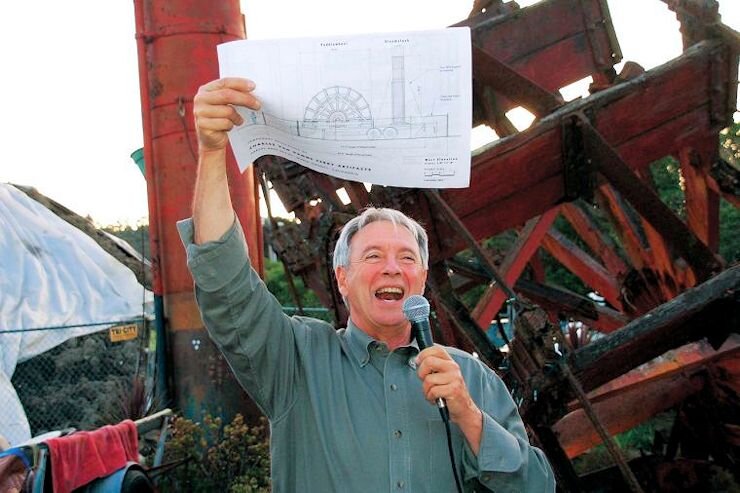

PHOTO FROM SAUSALITO HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Sausalito’s railroad terminal and ferry wharves in the early 1900s

Sausalito had an advantage because in 1909 the NWP completed the connection from the Sausalito line at Baltimore Park to detour on the mainline from Tiburon to San Rafael. With this “cut-off,” the railroad assigned virtually all passenger service, electric and steam trains, to the Sausalito ferry terminal. Tiburon remained the railroad’s freight and maintenance depot but lost most of its direct ferry service to San Francisco. A ferry shuttle was provided from Tiburon to Sausalito with a stop at Belvedere along the way. Yet, despite these changes, Sausalito experienced capacity problems at its terminal which left Tiburon in a position to continue its quest for direct ferry service to San Francisco.

As the automobile developed, successful ferry terminals needed excellent highway connections as well as a first-rate marine infrastructure. In 1909 Sausalito was included in the first State highway system, State Route (SR) 1 running from San Francisco north to Crescent City. By 1919 Tiburon, with its potential ferry connection to San Francisco, was also included. The State added SR 52, the shortest route in its system, just 5 miles in length, to connect SR 1 at Alto to the ferry terminal at Tiburon.

While both ferry terminals were nominally served by State highways, these roads were generally unpaved, narrow, curvy and poorly maintained. Marin jurisdictions passed several funding measures to improve streets and highways over the years.

State Route 1 was the primary north-south highway through Marin. Until 1930 SR 1 followed various local streets in Sausalito and country roads roughly along the west shore of Richardson Bay to today’s Camino Alto, Corte Madera Avenue, Magnolia Avenue, College Avenue, and Sir Frances Drake Boulevard to San Anselmo. At the Hub in San Anselmo a driver could choose to drive on either SR 1 east to San Rafael or on the county road west to Fairfax.

In 1930 SR 1 was realigned to follow today’s Hwy 101 alignment from Alto to San Rafael and paved to a width of 20 feet. The route became known as the Redwood Highway. SR 52 from Alto to the Tiburon ferry was completed with the construction of a 20-foot wide bituminous macadam surface roadway from Belvedere crossing to Tiburon on the current Tiburon Boulevard alignment.

And so, Tiburon won the race with Sausalito to have an improved all-paved State highway from its ferry terminal north to San Rafael. (SR 52 to SR 1 at Alto). As reported in the California Highways and Public Works magazine, with an automobile ferry at Tiburon, “This route [SR 52] will carry a considerable portion of the traffic using the Redwood Highway and will do much to alleviate the present congestion at the Sausalito [ferry] terminal.”

But, ironically, no San Francisco ferry service at Tiburon was provided. The Southern Pacific Golden Gate Ferries, Ltd., (GGF), reneged on its pledge to establish an automobile ferry within 60 days after completion of the highway. Many years later, in 1962, the Harbor Tug and Barge Company began a passenger ferry service at Tiburon. The railroad never did reestablish regular ferry service to San Francisco at Tiburon.

Meanwhile, into the 1930s the construction of SR 1 to the Sausalito ferry terminal continued. In 1933, SR 1 replaced a convoluted tortuous local street system from Manzanita/Waldo Point to Napa Street with a minimal curvature State highway (today’s Bridgeway). Prior to the improvement, the State Highway District Engineer called this local street “perhaps the most thoroughly disliked short section [1.3 miles], in so far as the traveling public is concerned, of heavily traveled highway to be found anywhere in the State.”

The State highway to the Sausalito ferry was finally finished in 1934. The portion of the route within the town limits was transferred from the State to the town. Over in Tiburon the State highway remains the primary street in town. Today’s Tiburon Boulevard —renumbered SR 131 in 1964-—still connects the Redwood Highway (U. S. Route 101) with the Tiburon ferry terminal.

It is interesting to note that with all the effort to complete the roads to the ferry terminals, just three years later, in 1937, the Golden Gate Bridge would open to car traffic, and ferry service would experience a rapid decline. All regularly scheduled ferry service from San Francisco to the North Bay would be terminated by 1941.